Words matter. The fact I declare this should come as no surprise, since I’ve been a writer for as long as I can remember.

Opinions matter, too. But they’re meaningful only if they’ve been subjected to a rigorous examination of their validity before being uttered. Otherwise, they’re merely pointless, irrelevant noise, adding nothing of substance to any conversation.

Persuasion also matters. How convincingly we present our opinions goes a long way in influencing those who hear and read them. Logic, structure, and sincerity bolster the likelihood that they will be well-received.

Most importantly, facts matter. The truth. Without accurate information, nothing we utter can add value to general discourse. Absent validated facts, the things we say and write can distort a conversation beyond all salvation. Misinformation—and worse, disinformation—are fatal to an honest exchange of views.

“But what is truth?” some will ask. “How do you know what the true facts are?”

My best answer is that truth is, to paraphrase Hemingway, a movable feast. Not movable in the sense of being deceitful or misleading to accommodate or justify a preconceived situation or viewpoint, but in the sense of being open to new discoveries that advance it beyond what is presently known.

For example, before the discovery of insulin in 1921, it was true that diabetes was an oft-fatal condition. Following that discovery, a significant advancement in medical knowledge, a more perfect truth was established, and sufferers began to live longer and healthier lives.

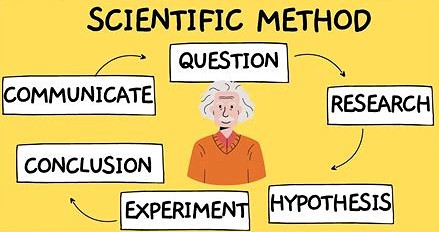

Any truth is established through a process that generally includes observation, questioning, hypothesis, testing, and conclusion. But given the transitory nature of truth in an evolving universe, every conclusion is itself subject to further observation, questioning, and so forth, until a more plausible definition is found. And this cycle, the scientific method, is endless.

Occasionally, special-interest groups will attempt to misrepresent generally-accepted truths by substituting non-scientific alternatives that have met none of these standards. They often base their claims on ‘alternative facts’. But at any given time, for any given subject, there is only one set of facts. And there is a difference between truths that no longer hold, that have been superseded in the face of newfound evidence, and outright falsehoods proclaimed by those who would deny proven truths for reasons of their own. Mendacity is not truth.

Mind you, all of us have reasons of our own for thinking or believing things we hold dear. I value different thoughts and beliefs now than I did in my youth, but they are undoubtedly more considered and tested than those earlier ones.

One of my favourite songs, made famous by Mary Hopkins, contains the lines: …we’d live the life we choose, we’d fight and never lose, for we were young and sure to have our way. But over time, I learned that we didn’t always have our way, and that many of the truths we espoused back then subsequently proved to be flawed.

The critical essence of facts, of truth, is that they are forever subject to scrutiny, that they must be evidence-based, that they are constantly in a state of flux as new discoveries come to light. Deliberate falsehoods are bound by none of those.

As a little boy, I believed the sun ‘came up’ in the morning because the rooster crowed, and ‘went down’ at night so I could go to sleep. That was how it appeared to me, and that is how those events were described by those around me. I eventually discovered the truth of the matter, but at the time I would have sworn upon my mother’s life that my childish perception was the truth.

“Is that really what you think?” a scornful, unkind friend could have asked me (although none did).

And I would have exclaimed, “I don’t think! I know!”

To which my friend could have replied, “I don’t think you know, either!” And he would have been right. I only thought I knew the truth.

This fictional anecdote points out a problem that can arise when we declare we think or believe something, and then, because we’ve declared it, assume it to be true, to be factual. If I think it rained because I had just washed my car, that does not make it the reason. Because I believe it’s bad luck to walk under a ladder or break a mirror does not make either of those things true.

One of the best pieces of advice I ever came across was: Don’t believe everything you think. And I try not to, although it is sometimes hard.

In politics, when one tries to ascertain the reason why certain things happen while others do not, there is a cynical piece of advice: follow the money.

In life, as one tries to discern the facts—the truth of any matter—my advice is to follow the evidence. Think critically, identify credible sources of information, and consider that information rationally. Words matter. Opinions matter. Persuasion matters. But above all, facts matter if we are to know the truth.

And the truth shall make us…well, you know.