Cogito, ergo sum—I think, therefore I am.

So opined René Descartes in 1637, in his famous work, Discourse on Method, demonstrating what he regarded as the first step in the acquisition of knowledge.

Of course, we don’t know that he was right, but because enough of us have come to believe his posit, it is almost universally accepted. Left unanswered is the question as to whether other living organisms are sentient, whether they also can think.

Some people believe they can—that creatures such as elephants, whales, and dogs are capable of thought—and they cite observed actions by these animals as proof of their belief. But what of other animals, or fish, and what of plants and rocks? To my knowledge, no one has as yet been able to prove (or disprove) the thesis that any lifeform other than human is capable of thought.

Regardless, it does seem likely that no form of life on our planet has attained the same level of high-order thinking that the human species has. And if any have, they have hidden it from us remarkably well. With physical brains somewhere between the largest and smallest in size among all living creatures, we humans appear to have outstripped them all in our capacity to think rationally.

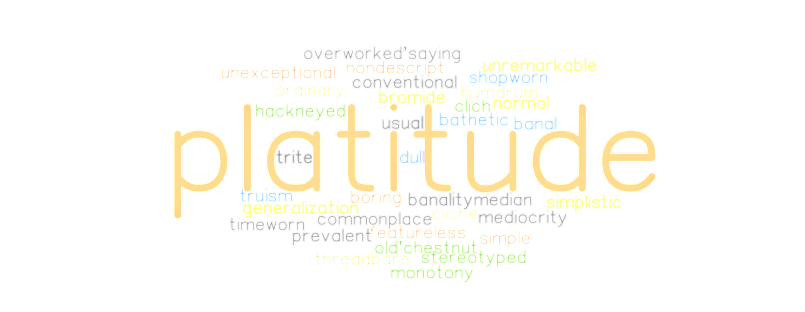

The capacity to think is what allows many of us to read widely, listen to diverse sources of information, and weigh the relative merits of differing schools of thought before deciding on a course of action—critical thinking. Alas, it is also what allows us to read narrowly (if at all), listen carelessly, and reject schools of thought that do not reflect our own preconceived notions.

Either way, thinking broadly or narrowly allows us to form opinions. And those opinions, whether supported by evidence or not, often morph into staunch beliefs if we don’t continue to think about them, to test them against emerging information. And inference plays a big role in that.

For example, if I waken one morning to the sound of thunder, and if I see flashes of lightning illuminating the drawn curtains of my bedroom, I might well infer that it’s raining outside. But I have no proof of that until I actually see (or feel, or smell, or taste) the tangible rain. I might throw open the curtains to discover there is no rain falling, despite the harbingers of storm; merely hearing and seeing those from inside my room would have drawn me into a false conclusion, yet one I believed until faced with proof of the opposite.

It points out the danger of choosing to believe everything we think, at least before we have evidence to support (or deny) our premises. As sentient beings, we are compelled to seek answers to the baffling phenomena we observe around us, to find reasons why situations unfold as they do, to explain the arcane mysteries that bedevil us—like where we came from and where we’re going.

Our world is replete with examples of how we have gone about this—in religion, science, engineering, medicine, music, literature, and so many other fields. The list of human accomplishments over the millennia is long and laudable. Errors have been made along the way, and corrections applied, but the steady march of knowledge-acquisition has been relentless.

Many of our ancestors, for instance, once believed (and some still do) that the earth was flat, that any who got too close to the edge would topple off the edge, fall into the void, and be lost forever. We know now, of course, that belief was untrue. As an amusing aside, the Flat Earth Society still boasts today in its brochures of having chapters of believers around the globe!

Still other folks believed once upon a time that our planet was at the centre of the known universe, that the moon and sun revolved around us; those people’s skills of observation, primitive by today’s standards, and their earnest thinking about those observations, led them to that conclusion. Yet, it was also not true.

Nevertheless, despite our many errors and missteps along the way, our capacity to think rationally—and to forever question our thinking—has allowed us to advance our collective knowledge. A key factor in continuing that progress is to avoid investing complete faith in any one thesis, regardless of its appeal at any given time; we must retain an appropriate level of skepticism in order to keep from falling into the acceptance of rigid dogma and blind ideology.

As George Carlin is reputed to have said, “Question everything!”

Another key is to continue testing theses to reinforce their viability, to find evidence of their truth (or falsity). But at the same time, we must remember that an absence of evidence of truth in the moment does not mean the same thing as evidence of an absence of truth. In other words, just because we don’t have the facts to prove the legitimacy of a thesis right now does not mean that thesis is untrue; it may mean simply that we haven’t as yet discovered the facts to validate it.

The advance of knowledge is, to paraphrase Hemingway, a movable feast.

An exception to prove the truth of any thesis can always be found, of course—something that demonstrates the general truth of a thing by seeming to contradict it. For instance: most of the teachers in that elementary school are female, and the one male teacher on staff is the exception that proves the rule. The thesis is factual.

We also know the true merit of any pudding is put to the test in the eating. But with one person’s taste being different from another’s, whose opinion is to be accepted as the truth? Any decision there must be regarded as opinion, not fact.

It is interesting to note that Descartes did not write, Cogito, credo quod cogitare, ergo non est recta—I think, I believe what I think, therefore it is right. Apparently, he understood that because we think something, even to the point of believing it, that does not necessarily make it true.

He also wrote, Non satis est habere bonum mentem; Pelagus res est ut bene—It is not enough to have a good mind; the main thing is to use it well.

Quaestio, semper quaestio—question, always question!