The latest weekly prompt from my writers’ group was to write a story based on a picture from the Florida Weekly Writing Contest. This is my entry—

To call it an insignificant garret would be to flatter it, tucked high on the south side of the federal building. From my desk, I can touch three walls if I stretch my arms, but I love my office. And I love the building!

Still visible on the frosted-glass door of my office are the words first inscribed fifty years ago: VULNERABILITY ASSESSMENT NATIONAL/INTERNATIONAL SECURITY HAZARDS. Since the opening of the office, I’ve been its sole occupant, first appointed in my mid-twenties by a Senator who owed my father a favor. Although our involvement in Vietnam had recently been suspended, the fear of security breaches in Congress was ever-present, so VANISH was established to monitor potential threats—a noble undertaking, though it never accomplished anything.

A longtime crony of the Senator was appointed as senior administrator, and I as his chief aide…his only aide, in fact. I never did meet the man, although I frequently saw pictures of him in the press with important-looking people. A portly, balding, bespectacled fellow, he occupied a prized, brightly-lit corner-office on the southwest corner of the third floor, two floors directly below my dormer-lit attic—a location whose door he never once darkened. For no other reason than that, I deemed him a wonderful boss.

In fairness, I never ventured into his office, either, our sole interface being the internal mail-delivery persons who moved around the building’s cavernous spaces like gray-clad ghosts. One of them told me there were only a few people who even knew my office existed up under the rafters.

Packets of classified files arrived each day to my in-tray, sat there untouched for a week before I slapped a RETURN sticker on them and transferred them to my out-tray, whence they were returned to the boss’s office. What happened next, or where they went from there, I had no clue; neither did I have any idea as to what I was expected to do with them whilst in my possession. Like so many crises du jour, they came, lingered awhile, then quickly vanished.

At the time of our appointments, the property-management folks planted a small tree beside the sidewalk directly below our windows—a sapling, really. Over the years, I’ve watched it burgeon to its current height of forty feet or more, where it now completely blocks the once-scenic view from the small balcony off the boss’s office. Given the utter lack of work-product or vision emanating from VANISH, I’ve often chuckled wryly about the irony of that.

Of course, the original boss is long-gone…or so I’ve been told. According to the security guard in the building’s lobby, a notice was distributed at the time of his leaving, but because I never opened files, I failed to see it. Apparently, his office was subdivided and is now occupied by three senior analysts. I don’t believe they know about me, though, as the files stopped coming to my garret some time ago. It’s almost as if I’ve vanished, too.

A decade back, I thought I might be required to surrender my sinecure, but the government changed the requirements for mandatory retirement, allowing me to linger on indefinitely. My paychecks—which used to be hand-delivered by the mail-persons before the introduction of online banking—have continued to appear in my bank account, and in amounts much greater than fifty years ago. I’m told I belong to a union, which perhaps explains that happy circumstance.

Happily also, I recently began to receive a generous pension check, along with a social security payment, deposited online each month. Due perhaps to a bookkeeping error somewhere in the vast bowels of the building, I reckon I am listed in personnel records as both active and retired. That, too, is ironic because, while never active in this job I love, I have never retired from it, either.

For years, I whiled away my working-hours playing chess-by-mail with other federal employees, or reading books borrowed from the large library in the basement, or chatting with window-washers and custodial staff who occasionally popped by. Now, of course, I play chess and read online right from my desktop computer.

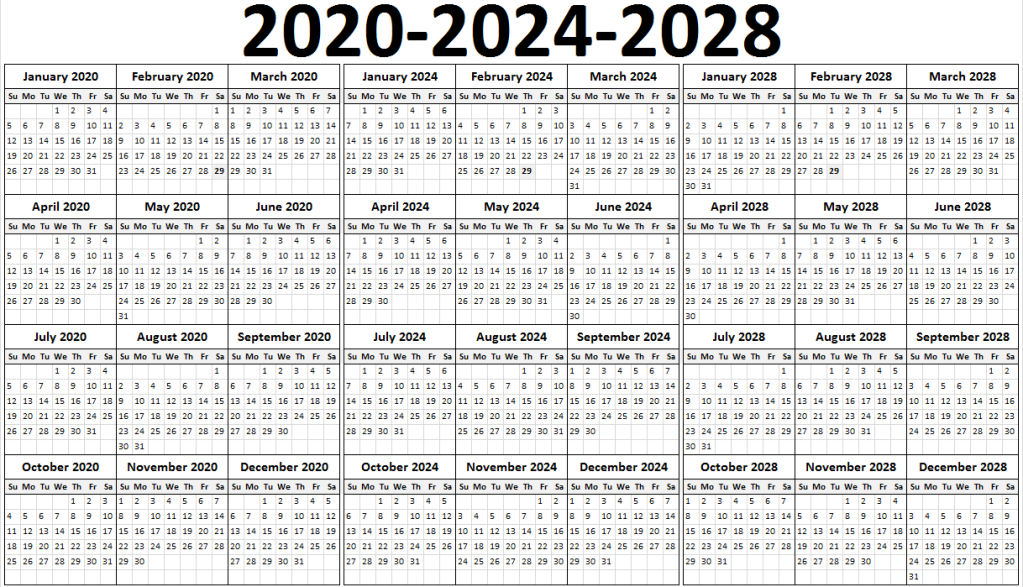

Civil service work is so fulfilling! I’ve served under nine administrations, beginning with Ford, and I’m still younger than the incumbent! There’s something in the air, I think, that makes me eager to show up for work each day.

I love this old building!

And I love VANISH!