For some readers, this post will appear in its entirety as an email in your inbox. To access the post in its true blog-setting, click on the title to read it.

The challenge in this piece was to have the story’s characters speak only the words of Shakespeare.

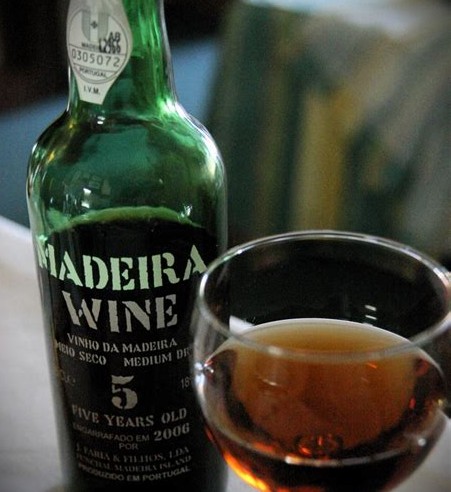

The three academics had been droning on in their usual fashion for more than an hour. Annabelle Fotheringham, widowed Professor Emeritus of the Classics, was still sipping daintily at her first glass of single-vintage Madeira. Her brother and colleague, Yorick Entwhistle, Dean of the College, was already on his third, yet mostly lucid. Arthur Wellesley, a great-great-great-grandson of the Duke of Wellington, and the College’s Distinguished Professor of English Literature for more than forty years, was savouring his second glass. All three friends appreciated the wine’s characteristic nuttiness, and its hints of caramel, toffee, marmalade, and raisins.

They were alone in the vaulted faculty lounge, each in a leather wingback chair in front of the stone fireplace that dominated the room. A dozen portraits of tweedy, long-since-departed faculty members gazed down austerely from musty portraits mounted on the walls between the leaded-glass windows that sheltered the lounge from a grey, drizzly, winter afternoon. Not one of the portraits was of a woman.

After packing his pipe with the fine Virginia tobacco he preferred, Wellesley struck a sulfurous match and puffed deeply, releasing plumes of bluish smoke into the cloistered air. Neither of his colleagues smoked, but they did enjoy the aroma that seemed to be soaked into the polished wooden walls of their surroundings.

“As flies to wanton boys are we to the gods,” Wellesley opined, replying to something Fotheringham had just said. “Lord, what fools these mortals be.”

“Misery acquaints a man with strange bedfellows,” Fotheringham said, nodding sagely. “Some are born great, some achieve greatness, and some have greatness thrust upon them.”

“Yes, but the devil can cite scripture for his purpose,” Entwhistle ventured. He lifted the decanter as he spoke, refilled his goblet. “There is a tide in the affairs of men, and we are such stuff as dreams are made on.”

The crackling fire was the only reply to that until Wellesley said, “We have seen better days, alas, but what’s done is done. When sorrows come, they come not as single spies, but in battalions.”

“For goodness’ sake, what a piece of work is a man!” Fotheringham scoffed. “To be or not to be, that is the question. All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.”

“Ay, there’s the rub,” Entwhistle replied. “But come what may, good men and true must give the devil his due.”

A blast of rain lashed the windows just then, followed by a thunderclap, as if the very devil he spoke of were seeking entry.

“Knock knock! Who’s there?” Wellesley chuckled, tapping the dottle from his pipe into the burnished, brass ashtray-stand beside his chair. “Blow, winds, and crack your cheeks…full of sound and fury! Come what may, even at the turning of the tide, the lark at heaven’s gate sings.”

“Alas and alack,” Fotheringham cried, “indeed, you set my teeth on edge. Misery acquaints a man with strange bedfellows, ‘tis true, and now is the winter of our discontent. But this is much ado about nothing.”

Busily repacking his pipe, Wellesley had no reply to that. The rain continued to pelt the windows, but the contrapuntal crackle of the fire served as a soothing counterpoint to its bluster.

“As good luck would have it, we bear a charmed life,” Entwhistle murmured, his words slightly slurred from the effects of the wine. “We are more honoured in the breach than in the observance, more sinned against than sinning. But the short and the long of it is that we shall shuffle off this mortal coil, so we must stiffen the sinews.” Gesturing around the room with one arm, he finished, “Here is not the be-all and the end-all.”

“’Tis neither here nor there,” Wellesley intoned, yellowed teeth clamped around his pipe-stem. “We have seen better days, but though this be madness, yet there is method in it.”

“A plague on both your houses!” Fotheringham declared, finishing her wine. “Come what may, ‘tis a foregone conclusion, cold comfort, a fool’s paradise. In my heart of hearts, I know all our yesterdays, filled with the milk of human kindness, will stand like greyhounds in the slips.”

Neither of her companions was entirely sure what she meant, and in truth, neither was she.

“The lady doth protest too much, methinks,” Entwhistle muttered as he added more Madeira to his goblet.

“Yorick, the better part of valour is discretion,” Wellesley cautioned him, afraid his friend might offend the lady. “The smallest worm will turn, being trodden on. Best you throw cold water on it.”

Entwhistle merely grumbled to himself, and his chin sagged onto his chest.

“Too much of a good thing!” Fotheringham said, pointing to Entwhistle’s goblet as he began to snore softly.

“Alas, poor Yorick! No more cakes and ale?” Wellesley smiled at his sleeping friend.

“And thereby hangs a tale, Arthur!” Fotheringham said archly as she rose to depart. “Such a sorry sight, my own flesh and blood!”

Wellesley got up, as well, and the two of them struggled to pull their inebriated colleague to his feet, his arms over their shoulders. “Once more unto the breach, dear friends, once more,” Wellesley sighed as they staggered with him to the door. “We cannot allow this to sully his spotless reputation.”

“Mum’s the word!” Fotheringham said. “The quality of mercy is not strained.”

“A ministering angel shall my sister be,” Entwhistle mumbled as they assisted him from the lounge.

Moments later, all that could be heard in the empty, cavernous room was the crackle of the fire and the relentless rain against the mullions.

All’s well that ends well, indeed.