Back in the late 1940’s, when I was in my formative years, a savvy and prescient social observer said, “We have met the enemy and he is us!”

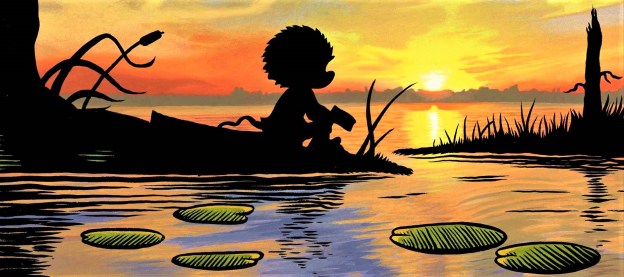

The speaker was Pogo Possum, an unprepossessing denizen of the Okefenokee Swamp, which straddles the border separating Florida from Georgia. During the next fifty years, Pogo would go on to become an American icon, famous the world over for his gentle, yet scathing, commentary on the world around us.

Strangely, many people today have never heard of him, but from the time I first took an interest in comic strips, Pogo was one of my favourites. And he remains that to this day—all the more so, considering where we presently find ourselves.

Pogo was the creation of Walt Kelly, a cartoonist extraordinaire who lived from 1913-1973, and it is Kelly’s inspiration that put words into the mouths of Pogo and his many friends and acquaintances in the swamp.

Among them were: Porky Pine, a gloomy, misanthropic soul, perhaps Pogo’s closest pal, an Okefenokee version of A.A. Milne’s Eeyore; Albert Alligator, extroverted and garrulous, often the comic foil for Pogo; Howland Owl, a self-proclaimed perfesser and fount of all knowledge; Churchy LaFemme, a hapless, superstitious mud turtle; Miz Mam’selle Hepzibah, a beautiful French skunk who often pined for Pogo; Beauregard Bugleboy, a hound dog who, as his grand name might suggest, fancied himself a dashing figure, often recounting tales of his own heroics in the third-person; and Miz Beaver, a corncob pipe-smoking washerwoman with scant regard for menfolk.

Pogo himself was a mild-mannered soul, described by Kelly as “the reasonable, patient, soft-hearted, naive, friendly person we all think we are.” Almost always portrayed hanging with friends, picnicking or fishing, he seemed the wisest, most laid-back, most down-to-earth swamp denizen, doggedly determined to avoid trouble. Alas, to his chagrin, he was often taken advantage of by those same friends.

The issues they faced in their wilderness home so many years ago presage many of those we face today—pollution, overcrowding, segregation and racism, and corrupt, self-interest politics. Listening to the utterances of the various characters on the concerns of their day resonates as much today as when they first spoke. Take, for example, the challenges facing governments as they tackle the Covid-19 scourge:

Y’see, when you start to lick a national problem you have to go after the fundamentables.

We are confronted with insurmountable opportunities.

Having lost sight of our objectives, we redoubled our efforts.

Or, think of the swelling cries from so many, bemoaning the encroachment of government on civil liberties during these trying times, refusing to comply with measures to ensure public safety:

I ain’t said much but I is been pushed around ee-nuf! I is gone stand up for my rights! And I got rights I ain’t hardly used yet!

The minority got us outnumbered.

The lovable swamp critters sometimes proposed radical solutions, just as many do today:

You want to cut down air pollution? Cut down the original source…breathin’!

Don’t take life so serious. It ain’t nohow permanent.

Occasionally, a familiar note of resignation crept into their musings:

Now is the time for all good men to come to.

If you can’t win, don’t join them; learn how to lose.

And, of course, there were commentaries on the political leaders of the day—some of which, I believe, apply to certain (unnamed) charlatans in power today:

Y’know, ol’ Albert [or a name of your choice] leads a life of noisy desperation.

In like a dimwit, out like a light.

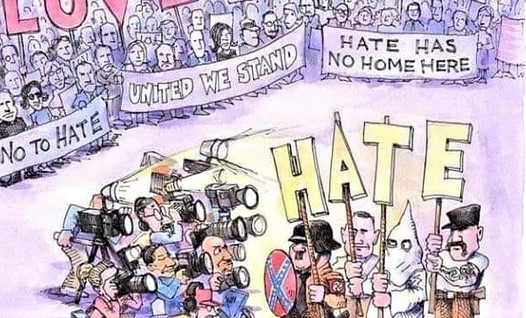

Of all the Okefenokee witticisms, though, the one I like best, and which seems truest of all today, is Pogo’s observation that the enemy is us. When I survey the planetary problems presently facing us—the most urgent of which right now is Covid-19—how many have we brought upon ourselves through our callous disregard for our global village and its residents?

To name a few of these enemies: world hunger, increasing poverty, global warming, pandemic outbreaks, nuclear proliferation, mass migration, and pollution of land, sea, and air.

To pose the question in a more positive way, how many of these same enemies could we actively and successfully confront through a united effort spread across all humankind?

Most, if not all, is the answer, I believe.

Sadly, however, I fear it may never be. For, as Pogo so eloquently told us in those bygone times, we have already met our greatest enemy.

And indeed, he is us!