For all readers, this post will first appear as an email in your inbox.

For those whose email contains a link, click on it to access the post in its true blog setting.

For those whose email simply shows the post in its entirety, click the title to read it in its true setting.

I was raised a Christian lad, not by proselytizing parents, but by a father and mother who passively practised the religion they’d been taught by their own parents. As an infant, I was baptized in the Church of England; as a boy, I attended Sunday School, where I learned the Anglican liturgy. In my early teens, I publicly professed my learned faith in a confirmation ceremony; as a young man, I married my bride in a Christian church.

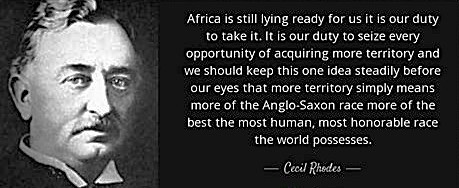

Growing up, I was enamoured of the tales of derring-do by British adventurers who set out to dominate the world—Richard the Lionheart and the Crusader knights; Sir Francis Drake and other explorers and privateers; Sir Cecil Rhodes and the rapacious conquerors of Africa and Asia. All of them ventured forth under the cross of St. George, ostensibly to bring Christianity to the heathen masses. Or so I was taught.

I wasn’t dissuaded by the troubling outcomes that sometimes occurred to me, arising from those teachings. For example, had I died before being baptized, I was taught I would not have gone to heaven; I was told that children of other faiths, unless they converted to Christianity, would not go to heaven; I believed none of us, being sinners, would go to heaven if we did not sincerely repent and swear never to repeat our sinful actions; and it was ingrained in me that those who did not go to heaven would be damned to eternal hellfire.

It didn’t dawn on me until much later how ludicrous it was that the God of love held dominion over me through fear. Still, I’ve never had doubts about the essential teachings of Jesus, as I understand them from the several writers of the Bible who have reported them—love; forgiveness; humility and service; empathy and trust; repentance and redemption; compassion and mercy. It seems to me that if everyone, Christian or not, practiced those teachings, the issues that plague our world would disappear.

From earliest times, my favourite part of being in church was listening to and singing the glorious hymns, accompanied by the mighty strains of a pipe organ. Because of the early, emotional indoctrination I experienced through my parents, they prickle my skin to this day when I hear them rendered—to name a few: Abide With Me; Blessed Assurance; Guide Me, O Thou Great Redeemer; Jerusalem; Joyful, Joyful, We Adore Thee; Nearer My God to Thee; O God, Our Help In Ages Past; and Rock of Ages.

A good number of hymns, I discovered later, were written by British lyricists and set to the melodies of classical composers, many of them Germanic. One of those, Glorious Things of Thee Are Spoken (by John Newton, who also wrote Amazing Grace), is sung to the same Joseph Haydn melody that graces the German national anthem, Deutschlandlied (formerly Deutschland über Alles).

Given the 20th century history of conflict between those two nations, I always found it strange that they shared a love for such glorious music. Even more so, I found it preposterous that soldiers of both Christian countries were killing each other on battlefields, in direct contravention of their shared God’s commandment.

Yes, God is with us! Nein, Gott ist mit uns!

But perhaps that isn’t so strange, given the militaristic character of many of those hymns. Take these lyrics for example—

Stand up, stand up for Jesus! ye soldiers of the cross;

Lift high His royal banner, it must not suffer loss:

From vict’ry unto vict’ry, His army shall He lead,

Till every foe is vanquished, and Christ is Lord indeed.

Implicit in those words is the instruction that good Christians must overthrow those who do not believe. I found that to be in contravention of the Christly teachings mentioned earlier, which always struck me as invitational rather than compulsory. I was taught, after all, that God had gifted us with free choice.

Mind you, George Duffield, Jr., the American clergyman who wrote the lyrics in 1858 and set them to an original melody by Franz Schubert, may not have intended them to sound militant or jingoistic. But that is how they ring in my ear. And it is such sentiments that crusaders and conquerors of the past cited to justify their conquests.

If you doubt it, consider also the lyrics of such hymns as Onward, Christian Soldiers, We’ll Go Out and Take the Land, or The World Must Be Taken For Jesus.

In fact, many Christian buccaneers and swashbucklers set out to plunder the world for reasons far more crass than what they professed. Bringing Christianity to the heathen masses was, at best, a by-product of their colonialist ravages, and at worst, an excuse for them. As for those Indigenous peoples subjected to the messianic zeal of 19th century Christian missionaries, I’ve always wondered how their forced conversions could be deemed proper when similar depredations imposed on Christian victims during the 8th century Moorish invasion of Europe were considered barbaric. Did both aggressions not have the same effects on those who suffered and died? Were they not the same thing, save for the religious faith driving them?

Might makes right, some say. To the victors go the spoils. And history—the history I grew up learning—was written by those victors. The synoptic gospels have Jesus saying, “Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar’s…” A venerable phrase translated from the Latin has Caesar claiming, “I came, I saw, I conquered!” The emphasis, of course, is on that final word.

So now, with more yesterdays accumulated than tomorrows to anticipate, I find I am no longer the Christian lad I once was…not with how Christianity, particularly the degraded, evangelical sort, has come to be defined in this 21st century. I do believe in free choice, and I choose not to believe Jesus was all about conquest and subjugation.

Further, I do believe in the wisdom of the aforementioned teachings of Christ, although I do not need the backing of a supernatural mythology to support my belief. I regard those as universal truths shared by Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Judaism, among other religions…and indeed, by many folk who profess no religion. Those teachings promote adherence to the Golden Rule, compassion for and kindness to others, the valuing of family and community, and the pursuit of a moral life.

I’ve long believed that the evils of this world are caused, for the most part, by extremism—unbridled nationalism, greedy capitalism, and apocalyptic religions. How might it be if only we gave those universal truths a chance to show what they could do instead?

In closing, lest this screed be mistaken for apostasy or advocacy, let me assure you it is no more than a statement of personal belief, refined over many years of observation and experience. Despite the sage admonition not to believe everything I think, I have always felt that believing in something is important, so as not to fall for anything.

The question, of course, is knowing what to believe. And for me, seeking that knowledge will be an ongoing journey until, inevitably, the road comes to an end.