Many years ago, my wife and I followed after the outgoing tide in the Bay of Fundy, along with our two young daughters, marvelling at the wonders we spied on the surface of the seabed. We laughed as our footprints gradually disappeared behind us in the spongy, soaked sand, and we strayed unmindfully farther and farther from shore.

When the tide reversed its course and began to flow back in, we dallied until the water was sloshing around our ankles before turning for shore. To our surprise, the rising surge outpaced our progress, the four of us able to move no faster than two pairs of tiny legs could muster. When the water got to our mid-calf level, we picked the girls up in our arms and picked up our pace, more than a touch anxious that we had underestimated our own capabilities.

We finally made it safely to higher, drier ground, but not before the water had soaked our buttocks, and to this day, I remember the knot of fear that had settled in my stomach, the certain knowledge that I was powerless against the relentless force of nature pursuing us shoreward.

Nature is like that—unrelenting, uncaring, inexorable. In our arrogance, we humans like to call it Mother Nature—in the same way we have anthropomorphized so many presumed deities and abiding mysteries. But nature is the furthest thing from a maternalistic, loving parent.

Since our planet first began its orbit around the sun, a natural environment has existed, an environment that eventually spawned life in its most primitive form. We humans are but a relatively-recent expression of that life-force, and we fancy ourselves its most highly-developed manifestation. From our very beginnings, we have sought to discover, understand, and control our surroundings—and to be fair, we have certainly done that to some extent.

Nevertheless, we find ourselves still subordinate to the forces of nature—feasts and famines, pestilence and disease, floods and droughts, tides and winds, wildfires and glacial melting, rising sea-levels, earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, to name a few. We have managed to mitigate the damage of such events to some degree, but we have not been able to eliminate them. In fact, the cataclysmic effects of nature’s actions have, over time, led to the extinction of many forms of life; taxonomists estimate that more than ninety-nine percent of all species that have ever existed are extinct. And so, the question naturally arises, could that same fate await our species?

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) publishes a Red List of Threatened Species, an inventory of the global conservation status and extinction risk of biological species. It includes 2.16 million current animal species, almost surely an underestimate, the most numerous of which is insects, almost half the total. In descending numerical order, the other groups are: molluscs, arachnids, crustaceans, fishes, reptiles, birds, amphibians, mammals, and corals.

We humans are just one species among the mammals, the second-smallest of the ten groups, a mere 0.003 percent of the total. Our group numbers more than 6500 recognized species, and of those, we are the most numerous (with rats being second).

In addition to the 2.16 million animal species on the planet, there are more than sixty thousand other species of life, including protozoa, plants, chromists, fungi, bacteria, and archaea. Among these, bacteria—the smallest, simplest, and most ancient cells—exert a tremendous influence on human life.

In our bodies, bacteria inhabit our digestive system, live on our skin, and contribute to our general wellbeing. But there is a downside, too; infectious diseases caused by bacteria have killed more than half of all humans who have ever lived, through pandemics such as the bubonic plague. Other examples of disease caused by bacteria include tuberculosis, whooping cough, sexually-transmitted infections, and e-coli. Because bacteria can reproduce themselves in less than an hour, mutations can emerge and accumulate rapidly, causing significant change, such as resistance to antibiotics.

Viruses, by contrast, are not living organisms. Rather, they are an assembly of different types of molecules that assume different shapes and sizes, but they can be as dangerous to human life as bacteria. Unlike bacteria, they cannot reproduce on their own, but need to enter a living cell to replicate and evolve. Once inside, they take over the cellular machinery of their host and force it to make new viruses. They can infect humans, other animals, plants, and even bacteria, and are able to evolve and jump from other animal forms to humans. They cause diseases like the flu, the formidable common cold, and SARS-CoV-2.

In the face of many perceived threats to our survival, a group of prominent researchers in Australia, the Commission for the Human Future, identified a list of risks to life on the planet: climate change, environmental decline leading to species extinction, nuclear weapons proliferation, resource scarcity (especially water), food insecurity, dangerous new technologies (such as AI), overpopulation, chemical pollution, pandemic disease, and denial and misinformation. Six of the ten are clearly within nature’s purview; the other four would be the result of human miscalculation.

What our species does about these ten existential threats in the next few years will determine whether present and future generations face a safe, sustainable, and prosperous future or the prospect of collapse and even extinction, the report said.

It also stated, Understanding science, evidence, and analysis will be key to adequately addressing the threats and finding solutions. An evidence-based approach has been needed for many years. Under-appreciating science and evidence leads to unmitigated risks…

Shaping [the human future] requires a collaborative, inclusive, and diverse discussion. We should heed advice from political and social scientists on how to engage all people in this conversation…

Imagination, creativity, and new narratives will be needed for challenges that test our civil society and humanity.

I confess to some doubt as to whether our species, tribalistic and combative as we are, will be able to manage that collaborative approach.

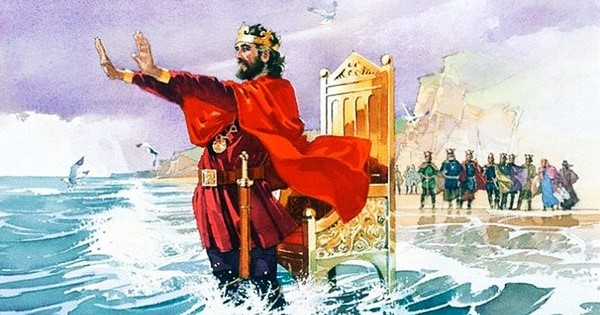

And I think back to the apocryphal story of King Canute, trying to hold back the tide—knowing full well he could not—in an attempt to teach his flattering courtiers that an earthly monarch could exert no control over the natural elements. True or not, the story illustrates the conceit of humankind in thinking we can ever be in control of nature.

As my wee family found out so long ago on the shores of the Bay of Fundy, we are most definitely not.

Nature will prevail, I fear. And the planet will continue its evolutionary journey around the sun, perhaps without us, until that star, too, is extinguished.