The weekly prompt from my Florida writers’ group was ‘believe it or not’, and this humourous tale is what I came up with—

“I swear to yez all, I seen the whole shivaree with me own eyes. Never woulda believed it otherwise!”

The statement was met with silence at first, and the big man’s two companions took a long swallow from the pints one of them, Rufus Mulaney, had added to his tab.

“Sure, an’ it don’t seem possible,” Mickey Finnerty said, wiping froth from his lip, the first to reply. “It only ever happened once before, so they say. An’ even that can’t be proved.”

“Don’t gotta prove it, me lad,” Sean O’Brien countered, savouring the bitter ale. “I seen it with me own eyes! Tha’s alla the proof I’ll be needin’.”

“Ye must think we’re all daft!” Mulaney declared. “Yer sittin’ there tellin’ us ye seen Seamus O’Malley die an’ then come back to life? Ye musta been well into yer cups! Such a thing just ain’t possible.”

“All good for you to say,” O’Brien sneered. “Ye were already passed out by then, breathin’ sawdust offa the floor when it happened. Any boyo who can’t hold his drink oughta not be correctin’ one who can!”

“Yer tellin’ me Rufe was there when it happened?” Finnerty said, looking back and forth between the two men.

“Aye, that he was,” O’Brien laughed, “right there ‘longside me an’ Seamus O’Malley…that is ‘til he slipped offa his stool an’ landed on his noggin. Lights out he was, ol’ Rufe.”

“That true, Rufe?” Finnerty said. “Ye took a drunken header in front of the whole establishment?”

“That’s what Sean tells me,” Mulaney admitted sheepishly. “I do remember spittin’ wood-chips outta me mouth when I managed to collect meself. All’s I know fer sure is I never saw ol’ Seamus croak an’ then come back.”

“Ah, ye gombeen!” O’Brien cried. “How could ye see anythin’ when ye was in a blackout? I’m tellin’ yez both, sure as I’m sittin’ here, Seamus O’Malley died an’ resurrected hisself, right in front of me eyes! Yez can believe it or not, I don’t give a shite.”

“Sure, an’ it’s wantin’ to believe ye I am,” Finnerty said, raising a hand to order another round for the group. “Gimme the wee details so’s I can better picture the grand second comin’.”

O’Brien waited ‘til the three of them had drunk deeply from the refreshed pints in front of them before answering. “Alright then, ye disbelievin’ dolts, here’s how it all went down. Me, Rufe, an’ Seamus were sittin’ here in this very spot, knockin’ back a few drafts after church last Sunday. Father Flanagan had been at his full-throttled best, talkin’ ‘bout how the good Lord raised his son from the dead on Easter Sunday, an’ just like always, the tale raised a considerable thirst in me an’ the lads.”

“Since when are you a church-goin’ man?” Finnerty asked.

“Since me good wife threatened to cut off me allowance,” O’Brien said. “But that ain’t no never-mind. The point is, we were just gettin’ the edge offa our thirst when who should come along but the Widow McGroarty, askin’ Seamus if he’d buy her a drink.”

“The Widow McGroarty?” Finnerty repeated. “She’s a mighty fine-lookin’ lass!”

“Aye, that she is!” O’Brien agreed with a leering smile. “O’Malley surely thinks so, too, an’ the word is him an’ her been…y’know, dancin’ the Irish jig, so to speak.”

“O’Malley?” Finnerty said, mouth agape. “What’s a fair colleen like herself see in a gombeen like him?”

“Who’s to say?” O’Brien said. “Anyways, right at that critical moment, good ol’ Rufe made a space for her at the bar by topplin’ offa his stool. She stepped right over the lad an’ hopped up beside us.”

“So, that’s why I musta missed what happened next,” Mulaney said, followed by another sip from his pint.

“Aye, ye missed the best part!” O’Brien chuckled into his beard. “Seamus ordered the Widow a shot an’ a beer-chaser, an’ after knockin’ ‘em both back, she leaned over an’ planted a smooch smack on his goober.”

“An’ that’s when he died?” Finnerty asked, caught up now in the story.

“Nah, that’s when he smooched her right back. He didn’t die ‘til a few minutes later when his ol’ lady walked into the pub lookin’ for him. We heard her voice callin’ his name afore she come through the door, an’ by then, Seamus was laid out flat beside Rufe, lookin’ for all the world like he was stone-cold dead!”

“Then what happened?” Finnerty asked.

“Me an’ the Widow McGroarty skedaddled outta the way,” O’Brien said. “We both thought Seamus had bought the farm right then an’ there, scared to his very death that the good Mrs. O’Malley mighta seen him smoochin’ the Widow.”

“An’ did she?” Mulaney asked, sincerely regretting that he’d passed out and missed the whole shebang.

“Nah,” O’Brien said, finishing off his pint. “All’s she saw was her husband lyin’ there on the floor. She figured he was passed-out drunk, so she grabbed him by his collar an’ gave his head a shakin’, the likes of which I hope I may never see again.”

“An’ then what?” Finnerty asked, so enthralled now that he did the unthinkable and signalled for yet another round on his tab.

“An’ right then,” O’Brien said, relishing the moment, “is when the resurrection occurred. Seamus scrambled to his feet, beggin’ forgiveness from the good woman, an’ allowed hisself to be dragged out the door by his ear. Dead one minute, brought back to life the next, just like I been tellin’ yez. Yez can believe it or not.”

“What about the fair Widow?” Mulaney asked. “I musta missed what happened to her, too.”

“Spare no worries for the lovely Widow McGroarty, lads,” O’Brien said. “Ever the gentleman, I made sure the lady got safely home to bed.”

“To bed?” Finnerty exclaimed. “Did yez…did yez…?”

“Sure, an’ that’s another story for another time, me boyos!” O’Brien said. “It’s thankful I am for the pints yez bought, but now I must be on me way.”

“He done it to us again, Rufe,” Finnerty said, watching as the big man left the pub. “Why do we fall for his blarney every time?”

There was no answer from Mulaney, however, who had seized that very moment to pass out yet again on the sawdust-covered floor.

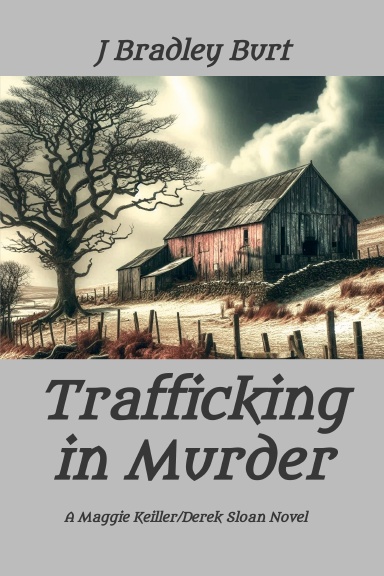

TOO EARLY FOR YOUR CHRISTMAS GIFTING?

TOO EARLY FOR YOUR CHRISTMAS GIFTING?