The thirteenth novel in my Maggie Keiller/Derek Sloan crime series will be published later this year, titled The Lonely, Silvery Rain. Here is an excerpted chapter from that book, slightly modified for this blog-post. If you have read previous books in the series, you will recognize the two characters here.

When Old Scratch, as Senator Nicholl disdainfully referred to death, came calling for the final time on a warm, drizzly, late-morning in October, he found Nicholl dozing in his favourite rocking chair on the wide, open-air verandah of his century home. The rain was thrumming on the shingled roof, dripping off the overhanging eaves, spilling like a shimmering, crystalline waterfall to the gardens below.

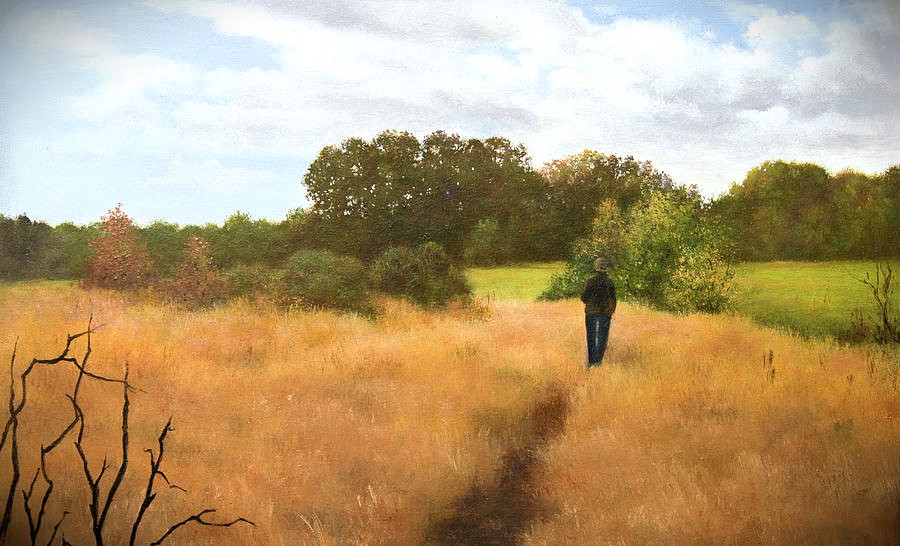

Before his spectral visitor crept in, Nicholl had been engrossed in a pleasant dream, delivering a stem-winder of a stump speech on another political campaign trail, surrounded by a throng of friends and constituents in someone’s farmyard. Balancing on a rickety, upside-down milking-bucket, he stood above everyone, so even those at the far reaches of the crowd could see him. He felt he’d never been in finer voice until, gearing up for the customary, full-throated culmination to his peroration, he discovered he’d forgotten what he was about to say. The shock was profound.

Groping vainly in his dream to remember the remarks eluding him, his mouth continued moving, though no sound emerged. Then, without warning, the bottom abruptly dropped away beneath him, as if someone had kicked the bucket out from under his feet. The world whirled and spun dizzyingly as he toppled, flinging his arms out in a futile attempt to catch himself. Despite the confusion and fear engulfing him, however, he still tried to finish, a campaigner to the end.

Wait! My speech! I’m purt’ near done…

But the dream turned nightmarish, and a misty, reddish haze descended across his eyes, and then…and then…

Senator Milford Nicholl, the simple, hometown boy-made-good, eased back in his rocking chair, sighed a fare-thee-well, and went to his eternal rest.

The many well-wishers who stopped in later that afternoon found Gloria, his wife of sixty years, shaken but composed, unbelieving but accepting, sad but relieved that her husband’s travails were over.

“He knew he was on borrowed time,” she told them softly, “and I could tell he knew his days were winding down. A wife always knows these things…” Her throat filled up, and she stopped to wipe away tears.

“Just a few days ago,” she whispered after a moment or two, summoning a small smile, “we talked about the possibility of one of us dying. And you know Milly’s sense of humour. He said something to the effect that he wasn’t afraid to die, he just didn’t want to be there when it happens.”

The mourners laughed at that, and a few shared more of the homespun witticisms they remembered flowing from Nicholl’s febrile mind. Eventually, Gloria told them she really would like time alone. “I’ll pray a little,” she said, “cry a little, laugh a little. There’ll be time enough later to reminisce some more. And I’ll call you if I need to, I promise.”

As everyone took their leave, Gloria waved from the verandah, then sat and rocked slowly in her husband’s favourite chair, his abandoned walker standing forsaken beside it. The rain was gentler now, but its sibilant pit-a-patting on the roof was still audible, its runoff still dripping off the eaves into the lush gardens below, covered by sodden, autumn-hued leaves. The unseasonably warm breeze caressed her, enveloping her in a blanket of solace.

She already understood she’d be missing Milly constantly from now on—his irrepressibility, his cornball turns-of-phrase, his devotion to the community—and most of all, his love for her, his very presence. She counted herself lucky to have been his partner and to have known such happiness.

Her grief over losing him would linger long, of course. She knew mourning is not something that can be quantified or measured by time. But at this particular moment, she was at peace with his passing, attuned to the happy memories she would cherish forever, resigned to the loneliness she knew would envelop her from time to time. They were all part of everyone’s journey through life.

But for right now, she was snuggled in Milly’s chair, at one with the inevitable rhythms of life and death, at one with herself, her soul in harmony with the comforting cadence of the rain.

The lonely, silvery rain.