[NOTE: SUBSCRIBERS WHO FOLLOW THIS BLOG RECEIVE EACH COMPLETE NEW POST IN THE BODY OF AN EMAIL. BUT IF YOU CLICK ON THE TITLE AT THE TOP OF EACH POST, YOU CAN READ THE PIECE IN ITS NATURAL ENVIRONMENT ON MY BLOG SITE. READERS NOT SUBSCRIBED AS FOLLOWERS RECEIVE A SHORT MESSAGE FROM ME WITH A LINK TO EACH NEW POST, WHICH TAKES YOU AUTOMATICALLY TO THE SITE.]

The latest weekly prompt from my Florida writers’ group was to write a story featuring the phrase, ‘You never know!’ This is my response—

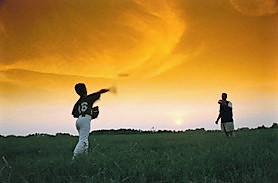

The ball leaps off the bat with a loud thwack! and soars skyward in a graceful parabola above the seven of us milling below, before curving back to earth, slicing right toward my little brother who prances nervously on the grass. He’s using the almost-new fielder’s glove I let him have for this occasion, while I use my beat-up old one.

I’m twelve years old, which makes Allan nine, and he’s a fair bit smaller. It’s the first time he’s been allowed to play ball with my friends—a game called 500, where we earn points for fielding balls hit to the outfield by a lone batter—and I’d coached him beforehand, especially emphasizing the need to call everyone off before making a catch so we don’t all collide under the ball.

“Just yell out to warn the guys you’re makin’ the catch,”I told him. “Everybody else will back off.”

Now, as the ball plunges toward him, I see him raise the glove over his head, his other hand poised beside it, just the way I taught him. “Call for it! Call for it!” I yell.

And he does…sort of. At the very last moment, he shouts, “Yours!” and ducks away. The rest of us watch disgustedly, disbelievingly, as the ball thuds into the grass, bounces once, and lies still.

“You don’t call Yours!” I yell at my brother, embarrassed in front of my friends. “You’re s’posed to call Mine! Mine! And then catch the ball!” Allan just offers that shamefaced grin he affects when he knows he’s disappointed me.

One of the other guys, a kid I don’t really like that much, gets right on my brother, shouting, “What a dork! What a chicken! What’re you even doin’ here?” Allan quails in the face of the attack, drops my glove on the ground, and trudges off to the sidelines, head down.

“Shut up, Gary!” I say to the kid, wondering if this is when we’re going to have that fight we both know is coming sooner or later. “Leave him alone!”

Gary glares at me, but chooses to let it drop. He tosses the ball into the batter, and we all trot back to the game—all but Allan, who sits on the grass to one side, holding the old glove I tossed to him when I reclaimed my newer one.

He’s not there when the game ends an hour or so later, so I head home without him. As I’m getting a glass of cold water at the kitchen sink, my mother says, “Where’s your brother? Supper’s in about twenty minutes.”

“I thought he came home,” I say. “I didn’t see him at the park when I left.”

“He’s probably still there,” she says. “Go find him, tell him it’s suppertime.”

With an exaggerated sigh, I make my way grumpily back to the park, which is only across the street from our house, but the trip seems like an unfair burden on me. Nobody else is there now, and I can’t see Allan anywhere. As I’m about to turn homeward, I hear a strangely-familiar noise coming from behind the maintenance shed on the far side of the ballfield.

Bump-badaba-badaba-badaba-thunk! Bump-badaba-badaba-badaba-thunk!

I trot across to the shed, and behind it I find Allan tossing a ball over and over onto the slanted roof of the shed. Each time he tosses it, the ball lands, rolls erratically down the torn and curled shingles, and bounces off the gutter, where my brother waits, trying earnestly to catch it in that beat-up glove.

Bump-badaba-badaba-badaba-thunk!

And now I remember why I recognized the sound! I used to practice the same drill by myself a few years ago, when I’d been told I wasn’t good enough to play with the big guys. Allan doesn’t know I’m there, so I watch for a few minutes, and I hear him quietly calling Mine! before each attempted catch. He drops more than a few because the gutter deflects the ball’s expected trajectory at the last moment, but he keeps trying.

And then he spots me. “What?” he says defensively. “You used to do this.”

“Yeah, I did,” I reply, ashamed now of my reaction in front of my friends earlier. “You wanta know a trick I learned to make it easier to catch ‘em?”

He nods, so I demonstrate how to hold back a bit as the ball rolls down the roof, then step into it at the last moment, tracking the bounce off the gutter. “It’s easier to catch the ball when you’re movin’ towards it,” I say. And we spend the next little while with me throwing the ball onto the roof and him catching it, more frequently now.

Bump-badaba-badaba-badaba-thunk!

And every time he moves in for the catch, he yells, “Mine!”

We’re interrupted all of a sudden by my father’s gruff voice right behind us. I don’t know how long he’s been standing there watching us, but he says, “Boys! Your mother’s waitin’ supper. We gotta go!”

Allan runs to him excitedly. “Didja see me catchin’ the ball, Dad? I’m catchin’ most of ‘em now! Jamie says I’m doin’ good! Didja see me?”

“Yeah, I saw you, son,” my father says, tousling my brother’s hair with one big hand. Throwing his other arm around my shoulder, he leads us back across the park.

“I’m gettin’ better, Dad,” Allan says. “You think the big guys will let me play with ‘em tomorrow?”

“You never know,” my father says, giving my shoulder an affectionate squeeze. “They might, but you never know.”

“Yeah, they will,” I say, “or they’ll be playin’ without me!” And my father squeezes my shoulder again.