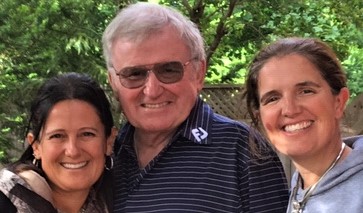

A good friend of mine died earlier this year, and I was asked to speak at a gathering of family and friends to celebrate his life.

This is what I had to say.

Every memory I have of my friend brings a smile to my face. Every one. It was fifty years ago that we first met, as young teachers. We clicked right away, and spent many hours playing tennis, going on ski-holidays with our wives, and spending many New Year’s Eves together. During all those occasions, we enjoyed a lot of delicious food washed down with cheap wine.

And although it might be hard to believe these many years later, legend has it that he and I were a lethal pass-and-catch combination on the flag-football field. Or so we told our wives.

Early on in our teaching careers, my friend and I contemplated applying for promotion to vice-principal. As the deadline grew near, however, he seemed somewhat hesitant about taking the step—having second thoughts because he really enjoyed working in the classroom. Many of his colleagues—and I for sure—encouraged him to go for it. We all thought he was more than ready, and I was sure we’d both be successful.

After much consideration, despite his reservations, he did apply. And guess what? My friend, the reluctant one, got that coveted promotion!

While I, the gung-ho guy, did not! Go figure!

But two good things immediately came out of that experience. The first was when my friend took me aside—I assumed to console me over my disappointment. Not so. He had an urgent, almost breathless tone to his voice when he was excited, and here’s what he said.

“Brad! Brad! Listen! Just because I’m a VP now, you don’t have to call me Sir!”

Of course, he said it with that mischievous, little smile I was so familiar with when he was having me on. I miss his sly, Irish sense of humour.

The second good thing from his promotion was that his first VP assignment was with the same principal who had hired me out of teachers’ college a few years earlier. That man showed my friend and me more about child-centred education than anyone else we ever worked for. He believed children came to school, not to be taught, but to learn; it was our job, therefore, not to teach them, but to guide them in their learning.

My friend took that philosophy to heart, as did I.

Our mutual mentor could be somewhat unpredictable, though. On the very first day of school that September, just before my friend’s very first staff meeting at the very first school where he was VP, where he knew almost no one on the staff, his new principal told him he would have to chair the meeting because something unexpected had come up that couldn’t wait.

Now, my friend was never, by nature, a cannonball-into-the-deep-end-of-the-pool sort of guy. He much preferred to examine every situation six ways from Sunday before committing himself to any course of action. He might eventually jump into that very pool, but not until he’d scoped it out thoroughly.

In this situation, however, the principal dropped the news on him at the very last moment, so you can imagine his reaction. He must have told me the story at least a dozen times over the years.

“Brad! Can you imagine? Just before the meeting was supposed to start! I was petrified! I had no idea what I was doing!”

But, as with everything he did, my friend carried it off with aplomb.

Over the years, he and I enjoyed professional-development opportunities together as our careers advanced, almost in parallel. Many of these were at annual conferences we attended, where we always roomed together. There were three reasons for that: one, we trusted each other not to drink too much and stumble back to our room in the wee, small hours; two, back in those days, neither one of us snored; and three, most important, we really liked each other’s company.

The two of us spent a lot of time at those retreats, walking the trails, talking about the challenges we faced as principals, about strategies for coping with those challenges, and about how we could make our schools into true centres for learning—for students and staff. We both benefited greatly from our professional affiliation, as well as from our friendship.

Our most influential professional development excursion was a real eye-opener for both of us. We had applied to visit four inner-city schools in a large American city, knowing we would probably be assigned at some point to similar special-needs schools in our own jurisdiction. I still remember stopping at a gas-station to ask directions to the first school—in those days, there was no GPS, but there were still service-station attendants.

The attendant said, “You two are going to that school?”

When we nodded eagerly, he pointed the way and said, “Keep your doors locked and your windows rolled-up!”

My friend and I looked at each other, wide-eyed, wondering what we might be getting into.

Within minutes, we found ourselves—two naïve waifs, far from home—driving through a neighbourhood in our bright-yellow rental car, hard to miss, where the only faces we saw around us belonged to people of colour. Nobody looked like us! Nobody! But a lot of them seemed to be looking at us.

We were never in any danger, but it was the first time in our lives, I think, that we both understood, at a gut-level, how it felt to be outside the mainstream—to be a person of colour in our predominantly white society—to be different, to be the other. It was a visceral awakening. Neither of us had ever experienced what it was like to be a visible-minority person until that day, when we realized we were.

The people in the schools were very gracious to these two trusting wayfarers who tried to absorb everything we were hearing and seeing. It was an experience that forever-after shaped our approach to children in our own schools who came from different backgrounds, different cultures, who had different skin-colour and strange names—all of whom wanted nothing more than to live and learn together in their adopted homeland.

I’m so glad I shared that experience and learned those lessons with my friend.

Part of his DNA, I think, was a natural empathy for the underdog in any situation; he always rooted for the little guy. Our experience in those inner-city schools certainly underscored and reinforced that quality.

Because of this empathy, it was no surprise that, later in his career, he became supervising principal for special education in our school board. In that role, he saw it as his mission to find the best learning environment for every child with special needs, sometimes with individualized instruction, where she or he could most closely realize their potential.

Finding placements for them was never just a numbers game. Like every principal worth their salt, my friend took these decisions personally. He took them to heart.

He was a good teacher, a good principal, and a good man.

It has been said that no one has ever truly died until the last person who remembers them has passed on. If that is so, then my friend will live a long time in the minds and hearts of his family and friends.

In fact, there are countless other people out there, people I shall never meet, people who remember my friend as their principal, or as their teacher. And I think many of them, when they sent their own children off to their first day of school, might have had this thought in mind.

“I hope they get a teacher like I had. I hope they get a teacher like him.”

And that is perhaps the greatest tribute.

I mentioned at the beginning that memories of my friend make me smile. And I’m smiling still because I knew him for fifty years, and was honoured that he counted me his friend.

Godspeed!