Since the turn of the century, my wife and I have been blessed to spend six months a year in Florida. During that period, we’ve lived under four American presidents—George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Donald Trump, and Joe Biden.

In that same timeframe in Canada, we’ve lived under four prime ministers—Jean Chretien, Paul Martin, Stephen Harper, and Justin Trudeau.

In Florida, we’ve made dozens of friends over that period, both fellow-Canadians and Americans, most of them snowbirds like us. Given the constraints of time and distance, and the vicissitudes of age, we no longer see many of them as often as once we did, alas; but we have never stopped considering them friends.

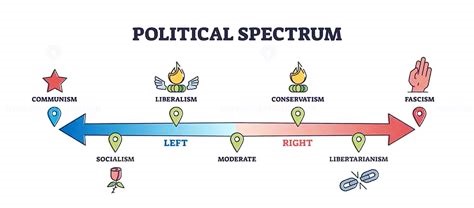

The majority, not all, are similar to us in the ideas we espouse, the values we cherish. My wife and I consider ourselves socially progressive, left-leaning, but close to the centre—more Liberal than PC in Canadian political terms, more Democrat than GOP in the American context. We instinctively distrust the fringe elements at both ends of the spectrum.

Some of our friends, though, are not so like-minded, being decidedly more right-of-centre than we. With them we generally avoid politically-fraught conversations, preferring amity and camaraderie to confrontation and unpleasantness. And it is indisputably true that all of them, regardless of viewpoint, are generous and kind in their dealings with us.

In the wider context, however—especially in the USA, but also in Canada to a lesser extent—we are currently witnessing an increasing divergence of opinion across social and political lines, accompanied by mistrust and hostility on both sides. Socially, the divergence is epitomized by the divide between the privileged few at the top of the socio-economic ladder and the huddled masses near the bottom. Politically, it is portrayed as the struggle between radical leftists (vilified by their foes as socialists) and ultra-right zealots (pilloried by their foes as fascists).

I must confess, my own political leanings are more socialist than fascist, more democratic than autocratic.

The struggle plays out across a large number of issues, a small sample of which includes: racism; LGBTQ2S+trans rights; reproductive rights; healthcare; voting rights; climate change; role and size of government; and religion. It is the first and last on this list that I deem most problematic in both countries.

Racism is a persistent concern. For many people in the USA, slavery is the unforgivable sin, the ineradicable stain on the national fabric, a transgression for which amends and restitution must be made. For some, it is a part of history best left forgotten, as if all is right with the world—see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil. With good will on both sides, however, these two groups could likely find common ground at some point.

But for others, a minority but a vocal one in both countries, racism remains a part of their ethos to this day—a deliberate allegiance to the notion of white supremacy. There is a great fear among such folk that they are being dispossessed of their rightful place, that their privilege is being taken from them. And they decry immigration policies that, in their opinion, indiscriminately admit people of colour.

Many of these people—perhaps too many—turn to demagogues to promote their cause, and those demagogues shamelessly court them to advance their own objectives.

Religion is another major problem. The separation of church and state, the partition between religious and civil authority, is a fundamental tenet in the governance of both the USA and Canada. Whether founded as democratic republic or parliamentary democracy, neither nation was envisaged by its founders to be a theocracy, ruled (or unduly influenced) by religious leaders.

Iran is a theocracy, as are Afghanistan, Saudi Arabia, Yemen, even Vatican City. But neither the USA nor Canada was intended to be one.

Yet today, in both countries, an ugly, religious fundamentalism has reared its head—a fundamentalism of a warped Christian persuasion, a fundamentalism, it must be said, distant from the teachings of the Christ regarding love, tolerance, repentance, forgiveness, and peace—all of which, mind you, are universal tenets found in the gospels of other major religions.

This fundamentalism preaches adherence to a narrow interpretation of biblical scripture, and seems (at least to this man) unduly restrictive of the rights of women. It is as if a pseudo-godly Godzilla has arisen to guide us to the Gilead foreseen by Margaret Atwood. I see the movement as an obscene fundamentalism that, in the words of the poet William Butler Yeats, slouches towards Bethlehem to be born.

I do not, of course, deny the freedom enjoyed by citizens of either country to freely practice their religions of choice, whether Christian or otherwise; I do, however, strongly decry all attempts by any group to foist their beliefs upon others for whom those beliefs do not apply.

And I do not for one moment believe that such religious fundamentalism should have any role at all in the governance of either of the countries in which I reside. But whether or not that will come to pass depends upon us.

In 2016, in the American presidential election, a large number of voters declined to cast a ballot. Whether that was through ignorance, through a belief their one vote would not make a difference, or because of a visceral, irrational hatred of Hillary Clinton, I do not know. Perhaps all of the above. But I do know what resulted from that election. And I do fear what might happen again in 2024 if ignorance, apathy, and hatred govern people’s actions.

Likewise in Canada, I fear ignorance, a belief one vote will not make a difference, or a visceral, irrational hatred of our current PM will yield a similar, catastrophic result in 2025.

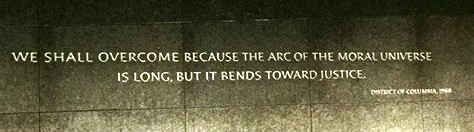

Martin Luther King, Jr. said in one of his speeches, the arc of the moral universe is long, but it bends toward justice. It is up to each of us, I suppose, to determine what constitutes justice and where it might best be found, both socially and politically. But whatever it is, and wherever it is, I believe it is forward, not backward; upward, not downward; toward the light, not into the darkness.

As Joni Mitchell famously sang, …don’t it always seem to go that you don’t know what you’ve got ‘til it’s gone!