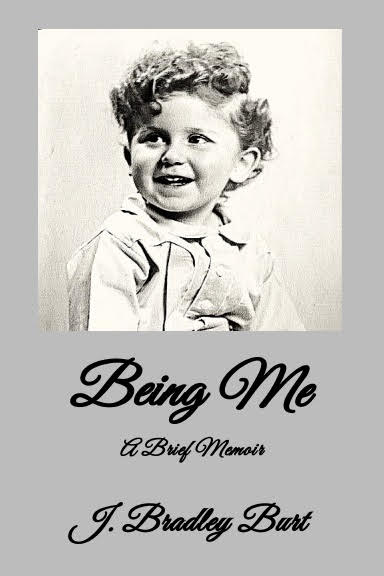

The weekly prompt from my Florida writers’ group was ‘Thou shalt not…’, and this is my response.

If the whole story appears in the body of your email, click the title to read it in its natural blog setting.

Managing to draw a final, feeble breath, I despair as it leaks slowly away. I try for another, but none comes. My eyes are slits, and through a gathering haze I see faces looming over my bed, concerned and curious.

“He’s gone,” a soft voice intones.

“I’m not! I’m not!” I cry wordlessly, soundlessly.

But then I am. And there is nothing…nothing…nothing…

I do not hear the words when they come. They emerge from my being, and I am become the words.

One. Moment. One. Moment.

Instinctively, I know the words refer to that same moment I have wished all my life to relive. And now it appears, on the brink of the afterlife, I am to have that chance.

I was fly-fishing with Hank, my twin brother, on the weekend before he was to marry the lovely Madison. She was the first person ever to come between us—Hank and Hal, Hal and Hank. But we both adored her.

We had fished this river so many times, it was like second nature—the boisterous sound of water rushing raucously over the rocks, the late-afternoon sunlight dancing on its rampaging surface, the fishing lines snaking overhead, gleaming in the waning light before the lures splashed into the current.

Hank was as happy as I had ever seen him. And indeed, why not? He was head over heels in love with Madison, his bride-to-be. As was I, alas, but it was he Maddie had chosen. And I had never wanted her more.

The fish were feeding in the cool evening, and Hank soon got a strike. As he moved to set the hook, he slipped on the moss-covered riverbed underfoot. I turned as he cried out, in time to see him hit his head on a rock. The current caught him, pulled him from the shallows, his arms flailing helplessly. I dropped my rod, charged after him, heedless of the precarious footing, and at the last moment, just as I fell myself, I clutched his outstretched hand.

“Hal! Hal! Help me!” he cried plaintively as he jounced and jigged in the powerful current. Blood streamed from the gash on his forehead. We locked eyes, and I could see he knew I would never let go.

But in that very instant, my unbidden thoughts fastened on Maddie and how distraught she would be if she were to lose him. To whom would she turn for solace, for comfort, perhaps eventually for love? And who would be better-suited than I to provide her that?

“Hal! Don’t let go! Don’t let go!”

We were struggling in deeper water now, where the current was stronger, tugging at my brother as if to tear him from my grasp.

“Hal! Don’t let go!”

But even as he implored me to save him, I did let go. And in a second, Hank was swept under, gone forever, and I swear I could hear Maddie’s forlorn weeping, taste her salty tears, feel her softness in my comforting arms.

And that was almost exactly how it played out. I cried copiously as I told everyone how I had tried in vain to save my brother. His body was found three days later, miles downstream, badly-battered by the river’s depredations, and he was buried with all due reverence.

Sixty years ago that was. And a scant two years after his tragic death, Maddie and I, each other’s chief comforters, were indeed wed. I have loved her with all I had to give ever since, but I have never quite forgiven myself for my treachery. Almost, but not quite. And perhaps because of my secret guilt, I have occasionally imagined a reservation in Maddie’s eyes about that day, although she has never questioned my account.

Nevertheless, I have never ceased to wonder what I would do if I could relive that one moment.

The good book tells us, Thou shalt not kill! But is that really what I did? Or was I just not able to hang on?

And now, wonder of wonders, so many years later, dead myself at last, I am being granted an opportunity to relive that moment. Is it a test to determine where I shall spend eternity? And with whom?

Hank and I are in the river once again, he has fallen and struck his head, is about to be carried away, and I have him in my grip. The bone-chilling water washes over us, and Hank calls frantically again, as he did back then.

“Hal! Save me! Don’t let go!”

But unlike the first time, I don’t have to wonder if I would win the beauteous Maddie’s love if Hank were to die. I already know the answer. He did die and she did become my wife, just as I had dared hope.

Should I change that outcome this second time around? Save my brother? Lose my Maddie? The final reckoning is at hand. The outcome is in my grasp.

And in that one moment, I make my decision.