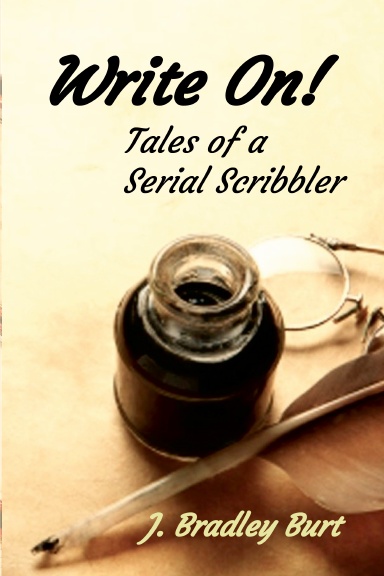

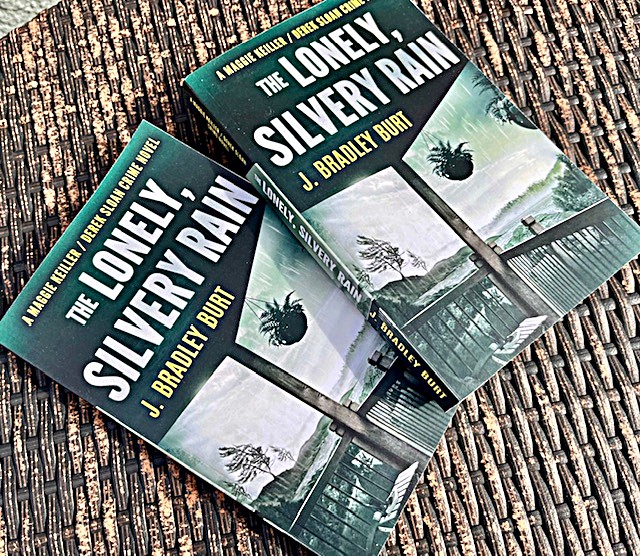

Otter & Osprey Press, a mainstream, Canadian publishing house (a division of Northern Forest Publishing), has released a second edition of my novel, The Lonely, Silvery Rain, to bookstores and online retailers. It’s available in both print and e-book formats, including Kindle.

This book is the thirteenth in my Maggie Keiller/Derek Sloan crime series, and the first to be offered by a Canadian publisher. As a crime-fiction novel, some of the portrayed events and language are intended for an adult audience…..but the story, as one editor commented, is kickass!

Set against a background of reconciliation efforts between government and the fictional Odishkwaagamii First Nation, a gripping story of betrayal and murder unfolds in Port Huntington, a small resort town on Georgian Bay. Vandalism, extortion, and violence are unleashed in the community as a number of personal grievances boil to the surface.

In 2018, the Ontario Superior Court of Justice awarded ten billion dollars to twenty-one First Nations in a vast area along the north shore of Lake Huron, to be paid equally by Canadian and Ontario governments. The settlement is compensation for unpaid annuities to those affected First Nations, annuities that were mandatory under the still-valid 1850 Robinson-Huron Treaty, whose terms committed the government to paying the affected First Nations annual stipends tied to actual resource revenues on their sovereign lands.

Over the years, billions of dollars in profits were extracted from First Nations lands for mining, timber, and fishing enterprises in Ontario, but the obligatory annual payments to First Nations were adjusted only once, thus depriving generations of First Nations people of revenues to which they were entitled.

Under the terms of the settlement, the Robinson Huron Treaty Litigation Committee, composed of Indigenous representatives, was tasked with determining how, and in what amounts, the funds would be distributed to the affected First Nations. While this story is a work of fiction, it is rooted in the very real question of how that money ought to be used. For the Odishkwaagamii, these debates boil over into deception and bloodshed.

Maggie Keiller and Derek Sloan are inextricably caught up in the turmoil, and it is only through their personal integrity and courage that they navigate the chaos. Determined as always to defend their Port Huntington community, and themselves, they work to ensure justice will prevail.

This safe, universal link will afford you a preview of the story, and direct access to your preferred online retailer—

https://geni.us/thelonelysilveryrain

After publishing my books through Lulu Press since 2007, an American print-on-demand firm, I’m thrilled that a Canadian publisher has picked up my work, and I encourage you to take a look at their website—

https://www.northernforestpublishing.com/homepage

I hope you’ll explore the link to my book, which I believe you will enjoy. Other titles in the Maggie Keiller/Derek Sloan series may be found at this safe link—