You’ve heard, I’m sure, of a murder of crows, a herd of cows, a gaggle of geese. You know of prides of lions, packs of wolves, and barrels of monkeys. You may even be familiar with a conspiracy of lemurs, a parliament of owls, and a convocation of eagles.

Almost every animal species has its own collective name, which is sometimes shared with other species.

Humans are no exception. We recognize band of brothers, pack of thieves, circle of friends. We may find ourselves from time to time as part of a flock of tourists, a panel of experts, or, sadly, a cortege of mourners. And there are many more I have learned only recently—sneer of butlers, feast of brewers, helix of geneticists, and one I especially love, slither of gossip columnists.

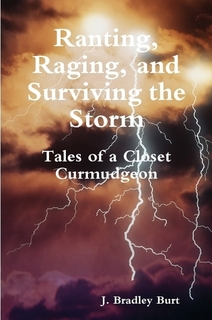

To my surprise and delight, I have recently been invited to become one of such a collective—a worship of writers. I had never heard the term before, though I have long worshipped the art of writing.

We meet once a week to read our responses to a writing prompt, each response no more than a page-and-a-half, and to offer constructive criticism of each other’s work. The responses are posted on a private blog, if their authors so choose, for all to enjoy and ponder again.

The prompt for this week, the first one for me, is separation. Each of us must write something to reflect that notion, knowing it can have many interpretations. Here is my first endeavour—

* * * * * *

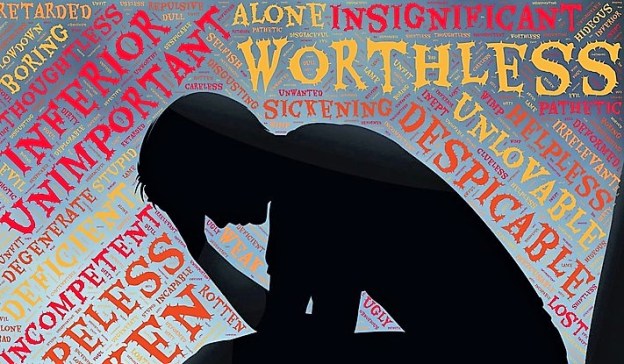

“There’s no easy way to say this, Harold,” the man behind the desk said. “So, I’ll come right out with it. “It’s been decided that we’re letting you go, effective today.”

“W-what?” I stammered, shifting from one foot to the other.

“You know we’ve been consolidating for some time,” he said. “Rightsizing. It’s been decided that we can no longer afford to carry your department.”

“But…but what about our readers?” I asked.

Staring at his hands folded carefully behind the nameplate in front of him—Don Mountbank, Managing Editor—he said, “Ruby will escort you out. You can take your personal belongings, of course, but nothing else. HR will be in touch with the separation details.”

Ruby, the fat security guard, moved next to me. I wondered why she’d been there when I first entered the office. Now I knew.

“Don, wait, this is crazy,” I said. “I’ve been with the paper for thirty-eight years. Longer than anybody. This is all I know. I’m a news-guy!”

Still not looking at me, Mountbank said, “Harold, this is very hard on me. Don’t make it even worse. Nothing you say is going to change a thing. It’s been decided.”

I felt countless eyes following us as Ruby walked me through the newsroom to my cubicle. Everything of my own was in the knapsack hanging on the back of my lopsided chair. I didn’t even open my desk.

At the employees’ door, Ruby said, “Sorry, Harold.”

The door banged shut and I was on the street. After almost forty years, the separation took no more time than that.

o – o – o – o – o

That was three months ago. I’m back in the newsroom today for the first time since. The few people still left, when they see me coming, bolt from their chairs, ducking, running. It’s not me they fear, of course. It’s the Winchester 94 I’m carrying, my deer-hunting rifle for more than twenty-five years.

It’s the first thing Don Mountbank sees when I burst into his office.

“Harold! What the hell…” He pushes his chair back from his desk, seeking to separate himself from whatever might be coming.

The young reporter he was meeting with rises slowly from her chair, hands splayed in front of her. She’d been hired shortly before my employment was terminated.

“Mary?” I say, checking my memory. When she nods, I say, “Sit down, Mary. Right there. Take out your phone and record everything that happens here. Audio only, no video. Got that?”

She nods again, eyes wide, and takes out her phone.

“Harold, what the hell are you doing, man?” Mountbank says, his voice cracking. “This is crazy! You know what will happen when the police find out?”

“Shut up, Don!” I say. “This is hard enough on me as it is. Don’t make it worse.”

His arms are raised now, as if to shield himself. “Harold, listen, you know it wasn’t personal. I tried to save you. I went to the wall for you. It wasn’t my decision.”

I point the Winchester at him. “Looks like you’re up against the wall again, Don.”

And then he soils himself. Both Mary and I lean back involuntarily, as if we can separate ourselves from the smell. Before he can say another word, I shoot him twice, once in the left knee, once in the right hand. The sound is louder than the flat Crack! I’m used to outdoors, the smell of cordite more pungent. He screams, writhing in his chair until he slides to the floor.

I turn to Mary. “This is your story to report,” I say. “Your exclusive. We’re going to leave now, you right in front of me. If you do exactly as I tell you, I won’t hurt you. Understand?”

She nods again, phone clutched tightly, and we head back to the deserted newsroom. As we approach my former cubicle, four police officers appear at the far end of the room. Ruby is with them, pointing at me.

POLICE! PUT DOWN THE GUN!

Mary and I freeze, the Winchester pointed at her back.

PUT DOWN THE GUN! PUT YOUR HANDS IN THE AIR!

Mary raises her arms.

“Mary,” I say softly. “This is your story. They’ll try to take it away from you, but don’t let them. You’re part of this, not separate from it. You report it, understand?”

When she nods, I say, “Okay, start walking away from me. Go slowly so you won’t scare the cops. You’ll be fine.”

When we are sufficiently separated, I take my finger off the trigger. The cops don’t see that. All they see is me still pointing the rifle at Mary.

SIR, PUT DOWN THE GUN! NOW!

But I don’t. Instead, I pivot towards them, the Winchester in firing position, no finger on the trigger. I’m struck immediately, three times, four, five, driving me backwards…

I’m on the floor…I see the ceiling tiles…the fluorescent lights…one is flickering…

Now I hear Mary screaming…

My chest hurts, it hurts…

And now…

* * * * * *

I don’t expect my new writer friends to worship the piece, but I’m eager to hear what they think of it. This is going to be fun.