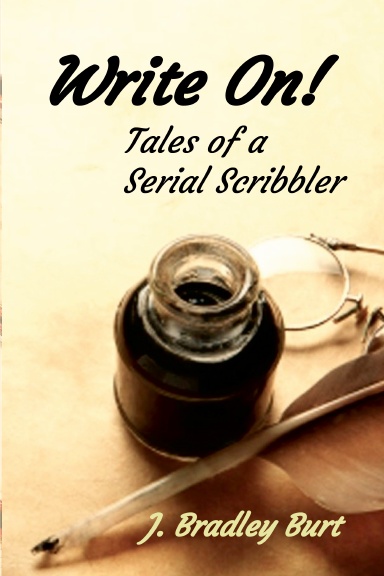

As many of you know, I recently published my ninth collection of stories and poems, something I’m very pleased about.

Titled Write On! Tales of a Serial Scribbler, it holds a trove of more than forty pieces I’ve written for the Pelican Pens, a group of enthusiastic writers here in southwest Florida. Each week, we meet to read our work to each other, to offer friendly encouragement, and to devise prompts to guide our creative juices for the following week.

After sending out my announcement the other day, it occurred to me that readers of this blog might like to read one of the short tales included in the book. Titled And Off We Go, it’s founded on the prompt—embarking on a fateful journey.

I’ve entered this tale in the Gulf Coast Writers Association 2024 writing contest, a competition where I was fortunate enough to take home first-place a year ago with a piece titled But He Didn’t!

I hope you’ll enjoy this preview of what lies in store for you in Write On! Tales of a Serial Scribbler. You can see more of the book, and my other published books, at this safe link—https://lulu.com/spotlight/precept

And Off We Go

“Shall we go?” The sepulchral voice is solemn, portentous, and it reverberates ominously in my ears.

Not yet…not yet! I’m not ready…

I hear other voices, too, softer voices…my daughters, named for our favourite flowers so many years ago. They’re talking quietly over me as I lie in a bed I cannot feel in a hospital room I cannot see, unable to speak or move.

“He can’t open his eyes,” Veronica says, “but I can see them moving behind his eyelids.”

“Yeah, I see that,” Jasmine agrees. “I think he can hear us.”

“Can you, Dad?” Veronica asks softly. “Can you hear us?”

Yes, yes, yes! I’m right here…

“He can’t answer you, Vee,” Jasmine says sorrowfully.

She’s right, I can’t. Everything was fine until…until…whatever day it was, I can’t remember…and that red wave washed over me, collapsing me on the floor for I don’t know how long. And now here I am, wherever this is.

“Shall we go?” the voice resounds in my ears again, a honeyed basso-profundo, not at all impatient, yet determined nonetheless.

No, not yet! It’s too soon…

“Keep stroking his hair, Jazz,” Veronica says. “He always liked that.”

I did always like it, but I can’t feel a thing now. I can only imagine how it feels, and the thought warms my heart. I laugh inwardly, knowing my hair must be all askew.

“I love you, Daddy,” Jasmine whispers. “I hope you know that.”

“He knows we love him, he knows,” Veronica says, and I imagine she is holding my arthritic hands in hers, gently massaging them, terribly weakened now when once they were so strong. But I can feel nothing.

I lifted you high in these hands, Vee, high up over my head. And Jazz, too! And now…and now…

“Shall we go?” The voice asks again, persistent though not offensive.

Not yet! No!

“You don’t have to worry about us, Dad,” Veronica whispers. “We’ll be fine.”

“She’s right, Daddy,” Jasmine adds. “You and Mummy were the best, and we’ll be just fine.”

I know, I know…but I don’t want to go…

They’re right, of course, they will be fine, both with their own wee families now. The little ones were here earlier with their daddies…at least I think they were…maybe not…but I’m sure I heard those four tiny voices telling me they love me. I wanted to say it back to them, to wrap my arms around them, but…

“And don’t forget, Dad,” Veronica continues, “Mum said she’d be waiting for you to find her, remember? She’ll be watching for you.”

Ah, their mother, my wife, my lifelong love…how I’ve missed her. Despite a valiant struggle against the disease that wasted her, she left us a few years ago. And yet, she never truly left us, you know? I wonder if Vee is right, if she really will be waiting there, wherever there is…my darling Clementine…

“Shall we go?” The voice is insistent, though not unkind.

No, please! Not yet…

“I’m sure Mummy’s been missing you, Daddy,” Jasmine murmurs, and I can hear the sob catching in her throat. “You were meant to be together for all time.”

“Exactly!” Veronica says, trying to lighten the mood. “Like apple pie and cheese! Like mustard and relish!” She laughs softly as she gropes for more examples.

Jasmine joins in her sister’s laughter, and my heart dances to the sounds of their lilting voices. “Yeah, or like Abbott and Costello!” she says. “Like Jack and Jill!”

“Lady and the Tramp!” Veronica offers, and the laughter grows louder. “Romeo and Juliet!”

“Omigod!” Jasmine gasps, their laughter rolling freely now. “Tweedledum and Tweedledee! Lancelot and Guinevere! Sweet and sour!”

“Yin and yang,” Veronica says, and they stop on that one, as if it’s the perfect one to describe me and Clemmie.

“Shall we go?” a voice asks again…but it’s a different voice this time. Frozen inside my immobile body, I cannot move, but I feel as if I’m turning around and there is Clemmie…as young and as fair as the first rose of summer. She’s standing in the midway at the State Fair, pointing at the Tunnel of Love attraction, the one where we had our first, tentative kiss, where the sense we’d found something special first dawned on us.

“Shall we go?” she asks again, and her eyes are sparkling, her smile warm and welcoming.

“It’s okay, Dad,” Veronica whispers, “it’s okay to go.”

“Goodbye, Daddy,” Jasmine breathes. “We love you.”

Goodbye, goodbye…I love you both…

And I reach for Clemmie’s hand, and off we go.