The melody was as familiar as my mother’s cheek on mine, the words had long ago been committed to heart. The singer was Aunt Marie, my mother’s older sister, her voice reedier now than in her youth, her pitch a trifle off. But the emotion she felt shone through in every chord.

You’ll never know just how much I love you,

You’ll never know just how much I care…

The occasion was the fiftieth anniversary of her marriage to Uncle Bob, and six of us were celebrating on the deck of my home overlooking the lake—my wife and I, my mother and father, and Marie and Bob. She was standing by the railing, singing to him as he sat in the old, wicker rocking-chair.

They’d married in the summer of 1942, enjoying a three-day honeymoon in Halifax, Nova Scotia, before saying a tearful goodbye when he was shipped overseas to join his regiment. It was three years before they saw each other again, when he returned home, battered but unbroken, a couple of weeks after V-E Day.

As my aunt sang on, her shoulder-length hair, salt and pepper now, fluffed and fell in the gentle breeze off the water.

…And if I tried, I still couldn’t hide my love for you,

Surely you know, for haven’t I told you so

A million or more times…

Within a month of returning home from Europe, Bob had gone off again, this time to the gold mines of Kirkland Lake in northern Ontario, where his degree in mining engineering had landed him a job. Marie joined him three months later, leaving her job and family in Toronto, and they stayed in that booming gold-town for the next twenty-five years.

I spent almost every summer of my childhood with them, for they never had children of their own. I thought of them as my second parents, certainly my favourite aunt and uncle, and to this day, the times I had with them rank among the most enjoyable of my life.

I used to hear them sing together after I’d been tucked into bed, she in a dusky alto, he in a clear tenor befitting his Irish heritage, and it was from them I developed my lifelong love of singing.

The last ten years of Bob’s career had brought them back to the city, working in the provincial Ministry of Mines. Although they were closer, I saw them less often, having married and begun a family of my own. But they remained as dear to me as ever.

Leaning against the railing by now, my aunt’s voice had begun to quaver, the sentiment of the song assailing her.

You went away and my heart went with you,

I speak your name in my every prayer…

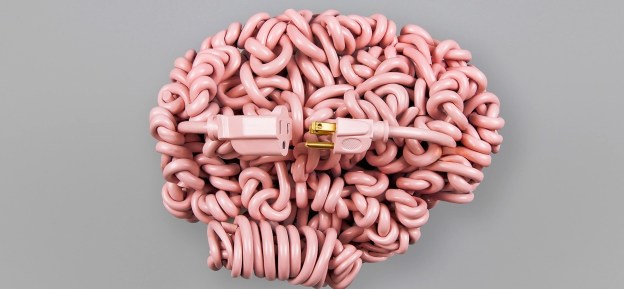

Within a few years of their retirement, my uncle had gone away again—this time to fight a war he could not win against the pernicious onset of dementia. But on that momentous day on the deck by the lake, he’d been with us for awhile—alert, engaged, and as happy as ever. Inevitably, though, he’d drifted off, as was happening much more often by then, his eyebrows knitted quizzically above a thousand-yard-stare we could never penetrate. He was a part of us still, yet apart from us irrevocably.

My aunt had continued her song, voice choked with emotion.

If there is some other way to prove that I love you,

I swear I don’t know how…

And she stopped right there, unable to finish, tears welling, rolling slowly down her weathered cheeks. None of us knew quite what to do, so we just sat there, watching her watch her husband, not a sound to be heard.

And then, the most touching thing happened. Bob had slowly turned toward his wife, perhaps wondering why the song had been cut off. Then, rising from the rocker, he’d shuffled over to stand in front of her. As their eyes joined, he lifted her hands to his shoulders and placed his own on either side of her waist.

And softly, he sang the closing lines to her.

You’ll never know

If you don’t…know…now.

Bob died before the year was out, mercifully for him, sadly for us. But I’ve never forgotten that song they shared on the day of their golden anniversary.

And I believe they both knew in that moment how very much they were loved.